A Heartfelt Tale: End-of-Life Dilemmas for Pets

Veterinary Ethicist Ponders Over the Fate of a Cherished Family Animal

Ryan J. Dougherty | Subscribe to Updates | Share on FB | Share on Twitter | Email this Post

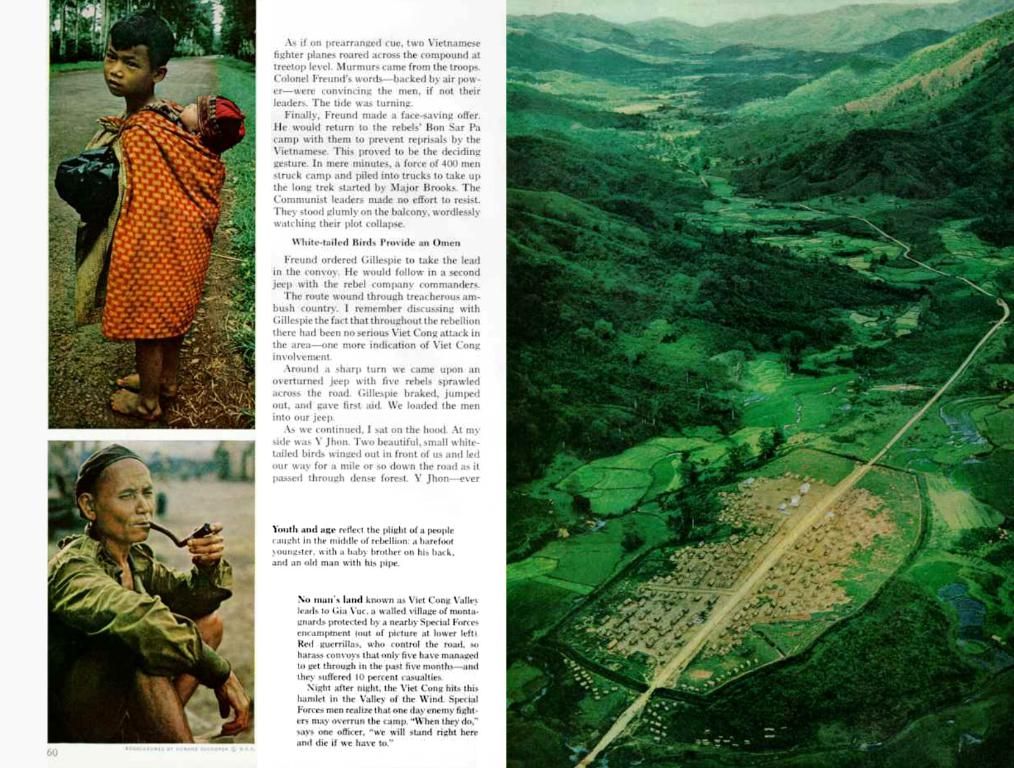

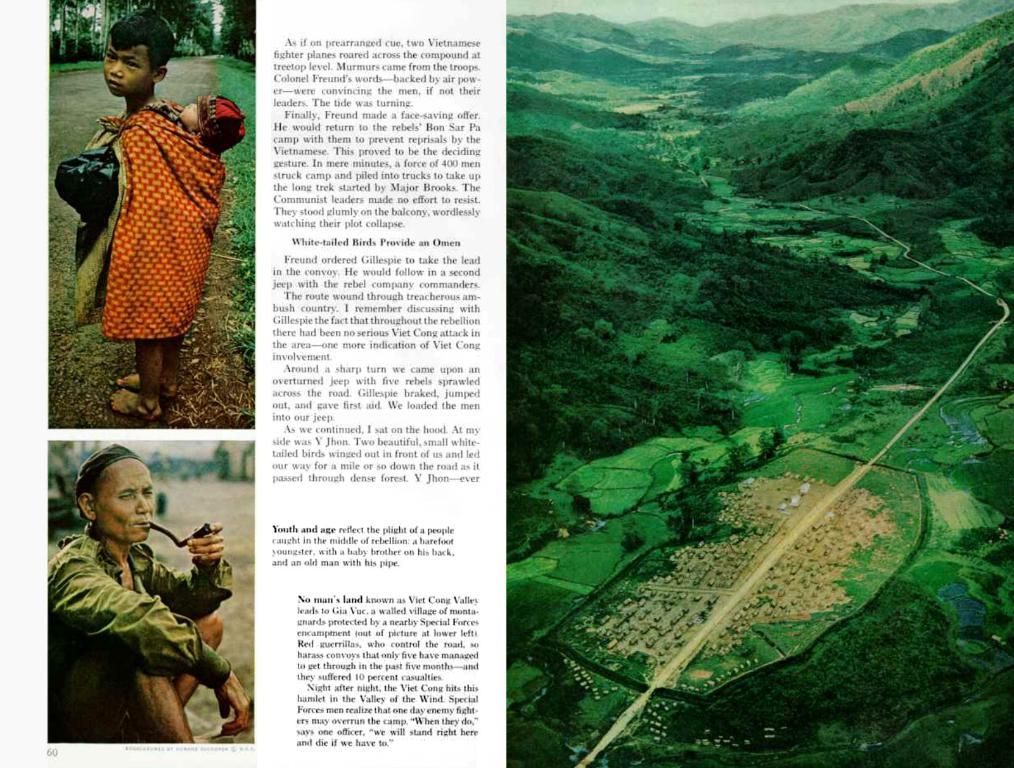

Back in the day, I sought my brother's advice, "Am I ready for a dog?" I balanced the perks against my doubts, examining my finances, work schedule, and canine know-how. But my real concern was if I could rise to the occasion, earn the trust, and guide my future furry friend. Adopting Sheba, a 4-year-old Siberian husky, was the start of a journey filled with lessons on stewardship, empathy, and, unfortunately, the cruel twist of fate in the face of end-of-life decisions.

Naively, I assumed that Sheba would instinctively follow my commands, but she thrived on understanding, patience, and rewards. Only by reading her body language, proactively guiding her behaviors, and establishing a predictable routine did I earn her trust. I wasn't her autocratic ruler but a steward shepherding her life on this earth.

Sheba's health took a turn for the worse in 2023. Kidney damage, likely stemming from a severe illness, left us with a grim diagnosis: repeated blood samples, imaging, and possibly a biopsy. Facing these decisions entwined me with complex ethical questions. As a clinical ethicist, I often delve into risks, benefits, and end-of-life treatments for terminal diseases, but Sheba's case was unique. Distancing myself from decisions regarding my beloved friend proved impossible. How could I decide for Sheba, who couldn't vocalize her preferences, where she stood on her values, or express her definition of quality life?

Tracing her past behaviors, I pondered her aversions to invasive procedures, her discomfort during examinations, and her distaste for medications. Her vintage years and unclear prospects of meaningful extension weighed heavily. Yet, could a dog "want" to forsake curative treatments in favor of comfort? Had I attributed human personhood to an animal, creating a false sense of duty? Or was it a simple cost-benefit analysis that prioritized her psychological comfort?

The ensuing months were a blur of joyful memories and burdensome responsibilities. I watched her bloom with happiness, playing with her kitten brother, Hermes, and finding contentment in her favorite routines. But the inevitable escape from her physiological decline loomed. When would it be ethical to euthanize Sheba? I fretted about depriving her of cherished moments if I acted too early, yet I feared prolonged, unnecessary suffering if I waited too long. Friends and family offered advice, some advocating for euthanasia on a "good day," while others shared their regret for ending their pets' lives "too soon."

Our final road trip took us back to Los Angeles, where Sheba and I had spent most of our time together. But our reunion was short-lived. Upon waking, I found her unable to stand, eat, or drink. She'd lost her sparkle and let out a deep sigh. Under the guidance of our veterinarian, we made the heart-wrenching decision to put her to sleep.

Now, six months after that fateful day, I reflect on the invaluable lessons that Sheba taught me. Her end-of-life experience underscored the importance of active listening, empathy, and making decisions with her, not for her. I felt a deep sense of moral obligation to honor her wishes, even when she couldn't voice them. In the end, I was grateful for the clinical knowledge and ethical frameworks I'd acquired as a clinical ethicist. But the most profound awareness came from within: the knowledge that Sheba had entrusted me with her life, and I, in turn, had vowed to cherish every moment, grant her joy, and deliver a peaceful departure.

Ryan J. Dougherty, PhD, MSW, HEC-C is a health care ethics consultant and scholar whose work explores the social systems shaping ethical decisions at the bedside. Ryan J. Dougherty on LinkedIn

[Photo: Sheba]

[1] Reffett, M. S. (2005). "Quality of Life Measures in Veterinary Medicine: Current Status and Future Directions." Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine, 19(1), 7-17.

[2] Zawistowski, S. M., Lansade, N., & Sasson, K. (2009). "Grief in Pet Ownership: Implications for Theories of Loss and Bereavement." Angewandte Klinische Psychologie, 36(1), 23–36.

[3] Melson, G., Yates, M. B., Zawistowski, S. M., & Carson, S. E. (2015). "The Ethics of Animal Euthanasia: Comparing Views of Veterinarians, Owners, and Society." Journal of Animal Ethics, 5(1), 1-26.

[4] McMillan, T. S., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2011). "On Being Good: Quality of Life and Animal Welfare." Society & Animals, 19(3), 242-256.

[5] Rollin, B. E. (1990). "The Rights of Animals: A Study in Moral Philosophy."Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of American Veterinarians.

Working as a clinical ethicist, I found myself pondering the same ethical dilemmas for my beloved Siberian husky, Sheba, as I did for patients afflicted by terminal diseases. During her battle with kidney damage, I questioned the treatment decisions based on her preferences and mental state, considering her aversions to invasive procedures, discomfort during examinations, and her distaste for medications.

In mental health and wellness, it is crucial to respect the autonomy of individuals, even non-human ones. Realizing this, I endeavored to honor Sheba's wishes for her quality of life, a principle that transcends species boundaries in the realm of science and health-and-wellness.