Marine Biologist John Bennett Studies Giant Squid Caught by Fishermen in 2007.

In a groundbreaking study published last month in the Journal of the Marine Biological Association of the United Kingdom, a team led by marine biologist Rui Rosa of the University of Lisbon in Portugal has redefined our understanding of the colossal squid, the world's largest invertebrate. Contrary to popular belief, the colossal squid is not an active or fearsome predator, but a slow-paced creature adapted to its cold, dark, and icy Antarctic home.

Previously, the colossal squid was associated with legends of terrible sea monsters, including the ship-wrestling kraken. However, the new data reveals that this deep-sea giant is more akin to a gelatinous drifter, with a slow metabolism and low energy requirements. The colossal squid's energy requirements are 300 to 600 times lower than those of warm-blooded whales, and its cold blood contributes significantly to its slow movements.

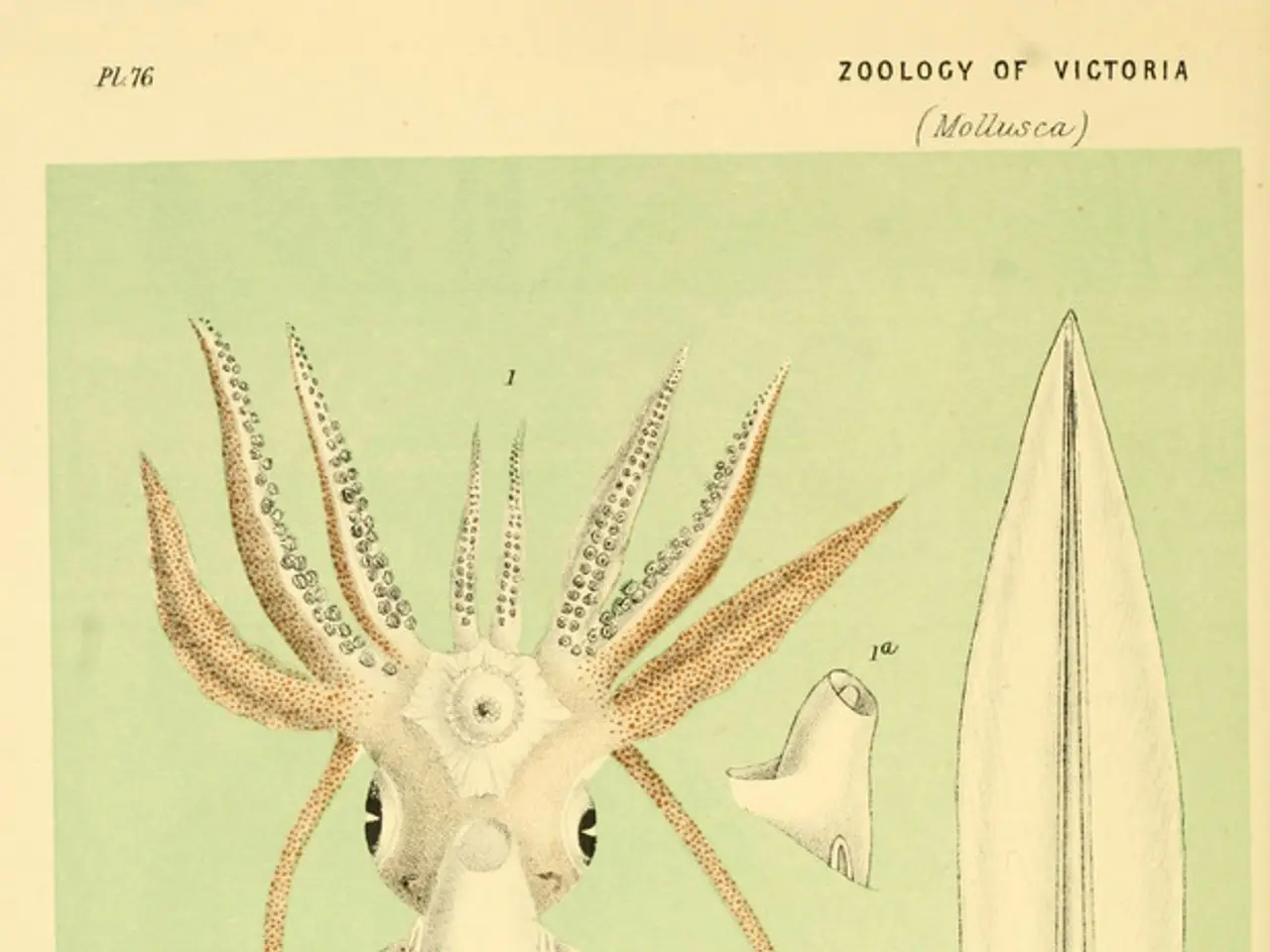

The study by Rosa and colleagues examined the physiologies and lifestyles of smaller, related squid species living in cold waters. Their findings suggest that the colossal squid's dinner plate-size eyes, an adaptation for avoiding predators such as sperm whales and sleeper sharks, may also play a role in its slow pace of life. The colossal squid's powerful beak, sucker-packed tentacles, and arms lined with razor-sharp claws are likely used for grabbing occasional passing fish or lying in ambush, rather than for active hunting.

The colossal squid lives in Antarctic waters at depths of about 6,560 feet (2,000 meters), making it difficult to observe and study in its natural environment. A 30-foot-long (10-meter-long) adult colossal squid was caught accidentally off Antarctica in 2007, providing scientists with valuable clues about these deep-sea giants.

While the colossal squid is believed to feed on large prey, including fish and other squid, recent studies do not explicitly suggest that it is a slow, sluggish drifter instead of an active predator. The lack of direct observational evidence means that scientists cannot definitively classify it as an active hunter or a passive drifter based on current research.

In contrast, the giant squid has been observed using visual cues to hunt, suggesting active predation. If similar observations could be made of the colossal squid, it would provide more insight into its behavior. Until then, its exact hunting strategy remains speculative.

The initial conclusions of scientists who dissected a captured squid in 2008 matched with the findings of the new study. The colossal squid is thought to be a "sit and float" predator, grabbing occasional passing fish or lying in ambush.

This new understanding of the colossal squid's lifestyle challenges the long-held belief of its ferocity and offers a fascinating glimpse into the life of one of the ocean's most enigmatic creatures.

- Future scientific expeditions to Antarctica, focusing on health-and-wellness, might help researchers better understand the slow-paced lifestyle of the colossal squid and its adaptation to the cold, dark ocean environment.

- The redefined image of the colossal squid, now understood as a passive drifter rather than an active predator, presents a unique opportunity for marine biology students to explore the science behind species adaptation in Antarctica.

- As the colossal squid's exact hunting strategy remains speculative, the ocean conservation community may wish to study this species more closely to ensure their continued health and wellness in the Antarctic ecosystem.